Resisting Antibiotics: Some Bacteria Get By With a Little Help From Their Friends

Antibiotic resistance is often in the news, as it threatens the effectiveness of one of the foundations of modern medicine. Usually, the concern is about resistance that is inherent to the bacteria, or else develops in bacteria through genetic changes. A paper published today in PLOS ONE suggests another possibility.

In “Chemical communication of antibiotic resistance by a highly resistant subpopulation of bacterial cells,” authors Omar El-Halfawy and Miguel Valvano reveal that some species of bacteria may help others in surviving an antibiotic attack. In addition, they were able to provide insight into the mechanics of how the bacteria perform this action.

The study began with an observation of the bacterial species Burkholderia cenocepacia, which typically grows in the soil but can infect people who have cystic fibrosis and those with compromised immune systems. The authors noted that a subpopulation of the species was more resistant to the antibiotic polymyxin B than other bacteria of the species. In other words, these resistant bacteria were more likely to survive after treatment with polymyxin B, and levels of antibiotics that killed the less resistant bacteria did not harm this (more resistant) subpopulation.

When the authors grew the more-resistant B. cenocepacia with another strain of bacteria called Pseudomonas aeruginosa (a disease-causing bacterium that can co-exist with B. cenocepacia), the P. aeruginosa were much more resistant to the antibiotic than when they grew in isolation.

Why might the P. aeruginosa be more resistant when they were in the presence of B. cenocepacia?

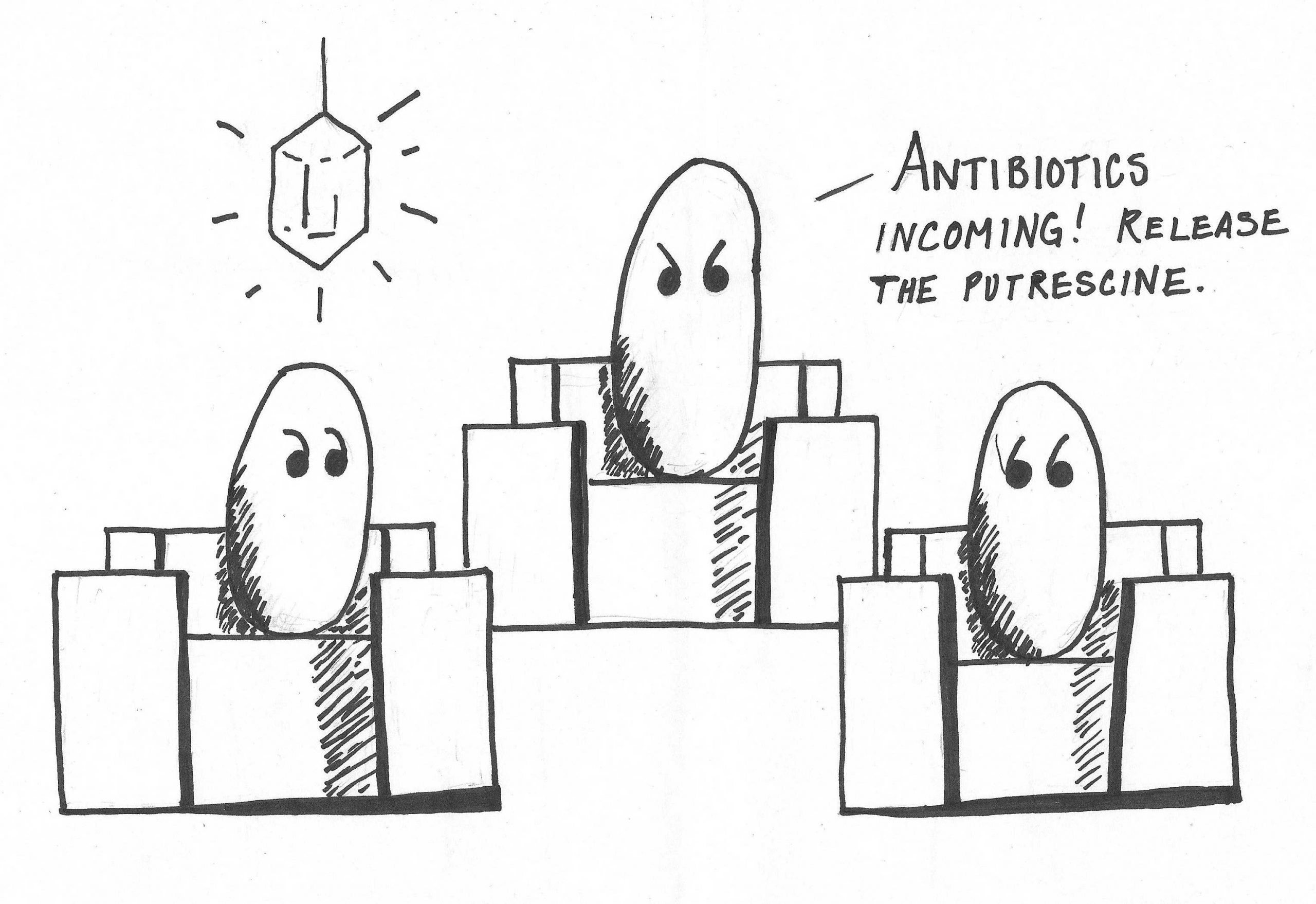

The authors suspected that the B. cenocepacia were releasing something into their environment that interfered with the action of the antibiotic, making it less potent. Experiments revealed that the bacteria were indeed secreting two proteins molecules associated with increased antibiotic resistance: putrescine (named for its putrid odor!) and Ycel, a protein whose function was previously unknown.

The large amounts of secreted putrescine blocked the antibiotics’ binding to the surface of the bacteria, and could make both B. cenocepacia and P.aeruginosa more resistant to polymyxin B when grown together.

Ycel, on the other hand, was able to bind to the antibiotic directly, presumably decreasing its potency. Ycel is predicted to bind amphiphilic molecules (such as detergents, which are attracted to both water and oil). Consistent with this prediction, the authors showed that Ycel had a protective effect against amphiphilic antibiotics and less of an effect against others.

These results have implications for combating the growing problem of antibiotic resistance. If we could prevent bacteria from making putrescine or Ycel, antibiotic treatments might be more effective, helping us eventually outflank resistance.

Citations: El-Halfawy OM, Valvano MA (2013) Chemical Communication of Antibiotic Resistance by a Highly Resistant Subpopulation of Bacterial Cells. PLoSONE 8(7): e68874. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068874

Bragonzi A, Farulla I, Paroni M, Twomey KB, Pirone L, et al. (2012) Modelling Co-Infection of the Cystic Fibrosis Lung by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cenocepacia Reveals Influences on Biofilm Formation and Host Response. PLoS ONE 7(12): e52330. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052330

Images: Pseudomonas aeruginosa doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066257