Reptilian Sibling Rivalry

Do you ever fight with your siblings? Unless you’re regularly biting, head-butting, and threatening each other all night long, things could probably be worse. The authors of a new PLOS ONE study investigate how well crocodilians get along with each other as youngsters.

Researchers observed seven species of hatchling and juvenile captive-raised crocodilians in Darwin, Australia and Chennai, India. The animals were divided into small groups and then introduced into new mixed water and land enclosures. The scientists counted, classified, and analyzed instances of aggressive interactions, postures and behavior among the animals. Because crocodilians are at their most active in the evenings and during the night (and at their most amiable during the day), the authors analyzed footage from 4pm until 8am the next morning.

Some but not all of the awesome aggressive behaviors the authors observed during the study included:

- Biting: “Jaws closed shut on an opponent.” Bites range from light mouthing to prolonged bites.

- Head pushing: “Head is pushed into an opponent.”

- Inflated posture: The crocodilian extends upward on its legs and arches its back downward to appear large and dominant. Other species also modify their posture in a similar fashion when challenged—two classic examples are cats and puffer fish.

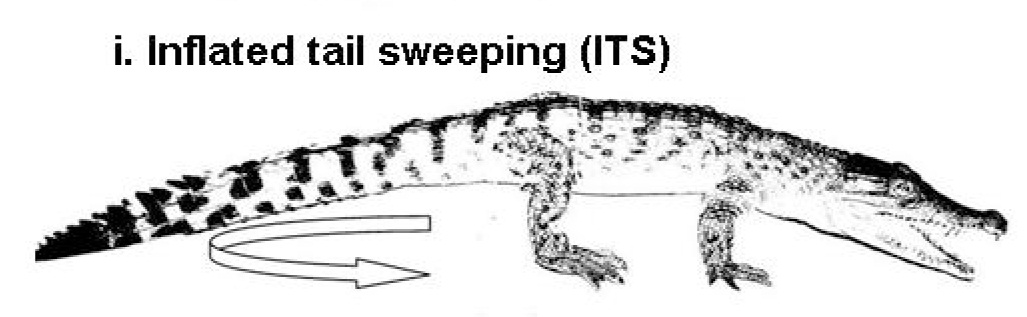

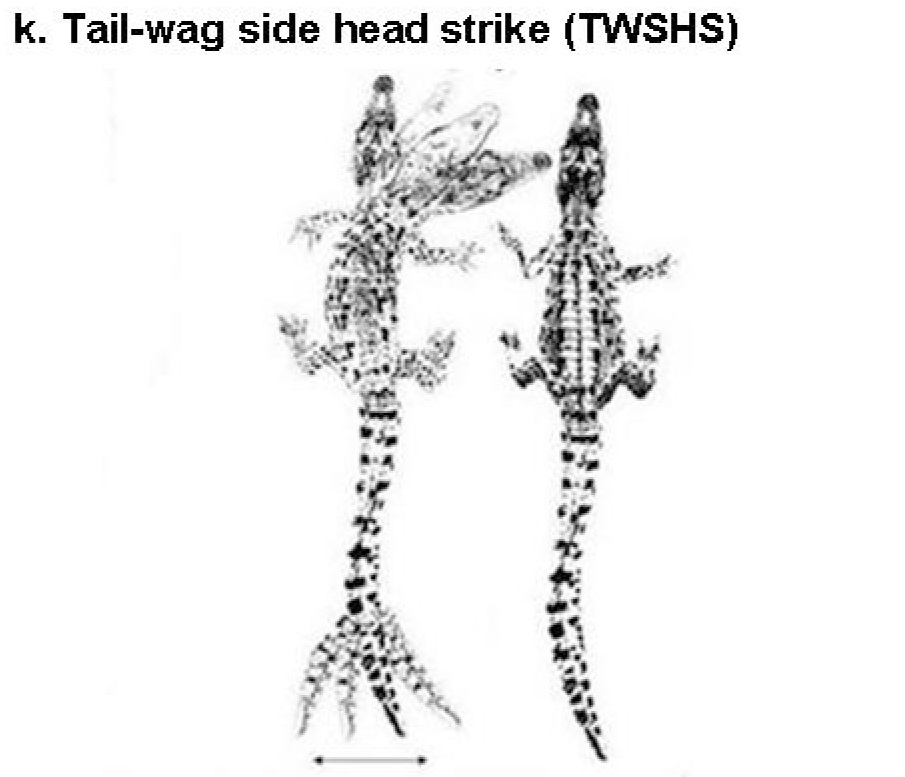

- Tail wagging: Crocodilians (like cats and many other animals) wag their tails as a way to signal and respond to aggression. They also sometimes tail wag as a windup to increase the force of a bite or a side head strike.

- Side head strikes: One individual thrusts his or her head sideways into another’s.

Based on the observed behaviors, the authors classified the seven species according to levels of aggression. The authors suggest that the significant overall differences in relative temperament likely arise from each species’ unique ecological environment and adaptations. Some species, like the American alligator, the gharial (native to India), and the freshwater crocodile, were highly tolerant of one another and had relatively few aggressive interactions. When these species did display aggressive behavior, the vast majority of aggressive incidents appeared to be accidental and low-intensity. Other more aggressive species, like the saltwater crocodile and the New Guinea crocodile, displayed pronounced dominance patterns and had a higher incidence of deliberate, intense aggression. These species used direct challenges like biting to establish dominance, and submissive behaviors such as raising the head into the air to yield. Bites and head pushes were the most common forms of aggressive contact across all the species, although many behaviors were species-specific. For example, slender-snouted crocodilians tended to avoid aggressive interactions and the most potentially damaging behaviors, perhaps due to a relatively higher risk of injury.

The researchers suggest that aggressive behavior in young crocodilians could be a survival strategy to help them learn social cues and minimize their chances of being injured in social settings. The extent of the hatchling’s aggression may affect how long it takes them to abandon their initial family groups. Babies will spend anywhere from a few weeks to a few years with siblings and a small number of adults, until (like so many humans) they leave their families and strike out on their own “due to a growing intolerance of each other.”

The authors indicate that this research may have implications for effectively rearing multiple species in captivity and may also inform the planning, management, and success of effective reintroduction and conservation programs worldwide.

Related Content:

Determinants of Habitat Selection by Hatchling Australian Freshwater Crocodiles

Why the Long Face? The Mechanics of Mandibular Symphysis Proportions in Crocodiles

Citation: Brien ML, Lang JW, Webb GJ, Stevenson C, Christian KA (2013) The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Agonistic Behaviour in Juvenile Crocodilians. PLoS ONE 8(12): e80872. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080872

Images: Siamese crocodiles picture by chem7, other pictures taken from Figure 1 of the published paper.