Unearthing the Environmental Impact of Cambodia’s Ancient City, Mahendraparvata

From the 9th to the mid-14th century, the region of Angkor in modern-day northern Cambodia was the capital of Khmer Empire and the largest preindustrial city in the world. Home to possibly more than three quarters of a million people, several different urban plans and reservoir systems, and impressive monuments like the temple of Angkor Wat (pictured from a bird’s-eye-view above), Angkor was the core of the Khmer Empire, which dominated Southeast Asia by the 11th century CE. Like many modern, booming cities, Angkor was fed by water sourced from another city.

Mahendraparvata, a hill-top site in the mountain range of Phnom Kulen, is significant as the birthplace of the Khmer Kingdom and as the seat of Angkor’s water supply. In 802 CE, Jayavarman II proclaimed himself the universal king of the Angkor region on the top of Mahendraparvata. Jayavarman’s ascension to power marked the unification of the Angkor region and the foundation of the Khmer Empire.

Until recently, however, little was known about the urban settlement of Mahendraparvata; a dense forest canopy obscures a great deal of the area’s archaeological landscape. To determine the extent of land use around Mahendraparvata, the authors of a recent PLOS ONE paper examined soil core samples taken from one of the Phnom Kulen region’s reservoirs.

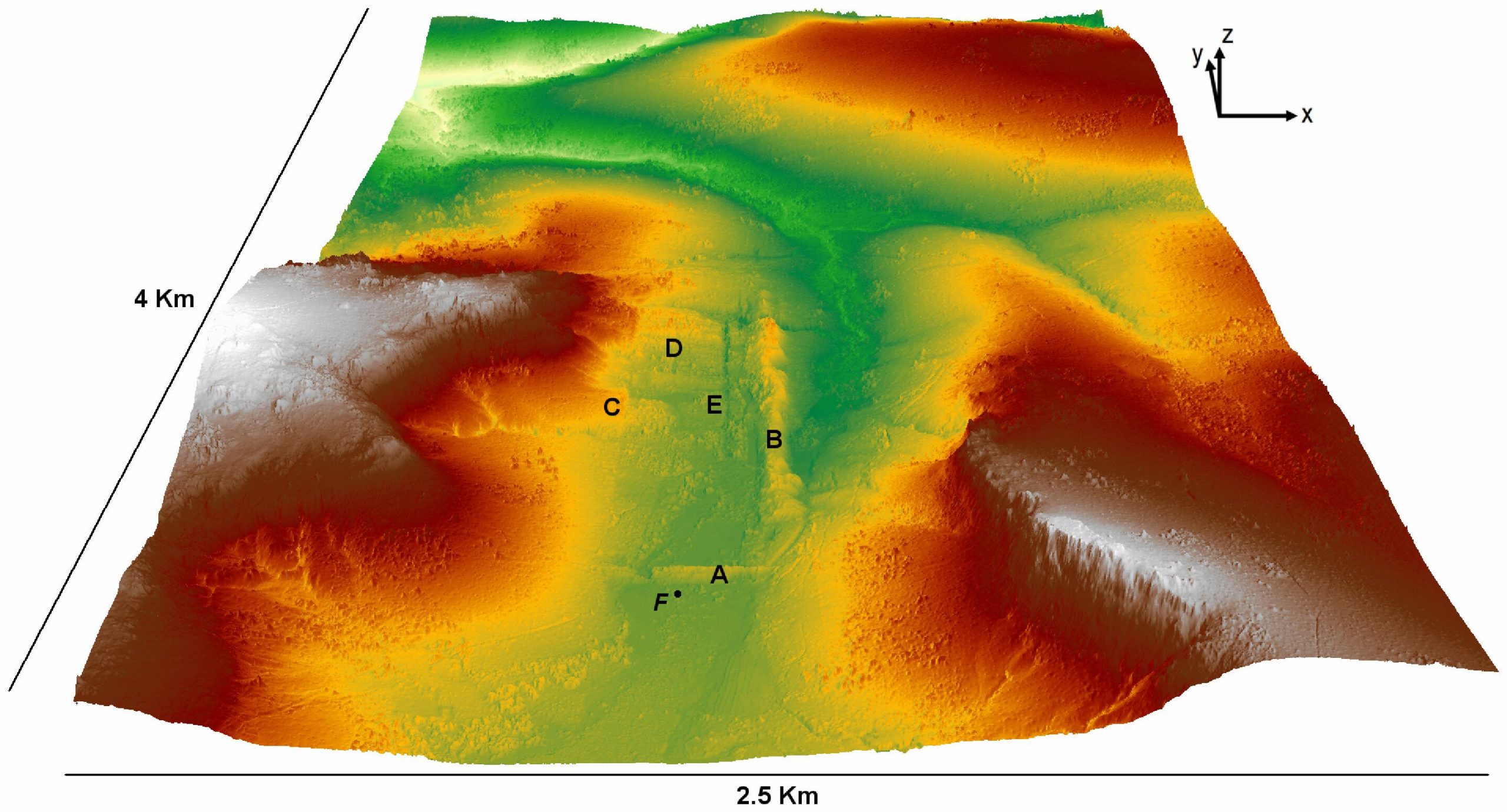

As Angkor’s source of water, Phnom Kulen’s archaeological landscape is littered with hydraulic structures, like dams, dykes, and reservoirs (points A, B, and E on the remote sensing digital image shown below), meant to store and direct Angkor’s water sources strategically. The researchers focused on an ancient reservoir upstream of the main river running north to south, now a swamp, to find evidence of intensive land use.

Core samples taken from the sediment of this ancient reservoir, point F on the image above, provided the researchers with chronological layers of earth containing organic materials, like wood, pollens, and spores, which could be assessed using radiocarbon dating.

By analyzing the sediment cores, researchers found that the reservoir was likely in use for about 400 years. Although the age of the reservoir itself remains inconclusive, sediment samples suggest that the valley was flooded in the mid-to-late 8th century CE, around the time Jayavarman II unified the area.

The authors found that medium-to-coarse sand deposition in the sediment samples beginning in the mid-9th century points to the presence of continual soil erosion, either from the surrounding hills or from the dyke itself, likely caused by deforestation in the area. By analyzing samples from the late 11th century, the authors found that the last and largest episode of erosion occurred, a possible result of intensive land use.

The researchers suggest that deforestation, as evidenced by soil erosion, implies that “settlement on Mahendraparvata was not only spatially extensive but temporally enduring.” In other words, the estimated extent of deforestation by continual sand deposits from the mid-9th century to the late-11th century in core samples indicates that Mahendraparvata was home to a large and thriving urban network in need of resources.

However, an increase in pollen spores dated to the 11th century, followed by the establishment of swamp forests in the early to mid-12th century in the reservoir, reflects that, by this time, the reservoir had fallen out of use, perhaps linked to changes in water management throughout the broader area, and possible population decline nearby. According to mid-16th century samples, the swamp flora around this time appears to have developed into the swamp flora seen today in the ruins of Mahendraparvata.

For some 400 years, the Phnom Kulen mountains acted as the main source of water for the Angkor region. The change of water management practices in the Phnom Kulen region has implications for the water supply to Angkor itself. In sum, by examining core samples drawn from one of Phnom Kulen’s ancient reservoirs, authors were able to explore an archaeological landscape that is still largely hidden and a history still mainly obscured by time. The potential link between the rise and fall of urban life in the Angkor region and the use of reservoirs like the one used in this study helps to unearth a little bit more about the the Khmer Kingdom and the marked environmental impact of Mahendraparvata.

Citation: Penny D, Chevance J-B, Tang D, De Greef S (2014) The Environmental Impact of Cambodia’s Ancient City of Mahendraparvata (Phnom Kulen). PLoS ONE 9(1): e84252. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084252

Image 1: Angkor Wat by Mark McElroy

Image 2: journal.pone.0084252

Image 3: journal.pone.0084252