For Yeast’s Sake: The Benefits of Eating Cheese, Chocolate, and Wine

Yeast—including more than 1500 species that make up 1% of all known fungi—plays an important role in the existence of many of our favorite foods. With a job in everything from cheese making to alcohol production to cocoa preparation, humans could not produce such diverse food products without this microscopic, unicellular sous-chef. While we have long been aware of our dependence on yeast, new research in PLOS ONE suggests that some strains of yeast would not be the same without us, either.

Studies have previously shown how our historical use of yeast has affected the evolution of one of the most commonly used species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, creating different strains that are used for different purposes (bread, wine, and so on). To further investigate our influence on yeast, researchers from the University of Bordeaux, France, took a look at a different yeast species of recent commercial interest, Torulaspora delbrueckii. In mapping the T. delbrueckii family tree, the authors show not only that human intervention played a major role in the shaping of this species, but they provide us with valuable information for further improving this yeast as a tool for food production.

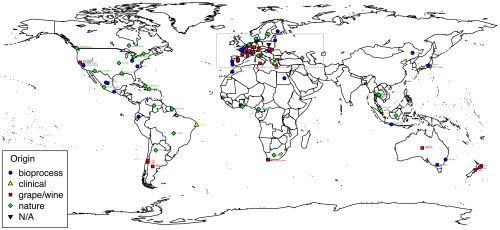

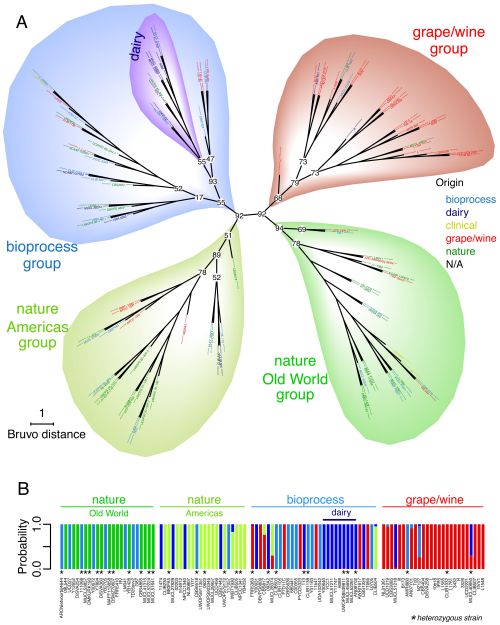

The authors collected 110 strains of T. delbrueckii from global sources of wine grapes, baked goods, dairy products, and fermented beverages. Possible microsatellites, or repeating sequences of base pairs (like A-T and G-C), were found in one strain’s DNA and used to create tools that would identify similar sequences in the other strains. They used the results to pinpoint eight different microsatellite markers (base pair sequences) that were shared by some strains but not others to measure genetic variation in the T. delbrueckii family. The composition of each strain was measured using microchip electrophoresis, a process in which DNA fragments migrate through a gel containing an electric field, which helps researchers separate the fragments according to size. As each strain’s microsatellite markers were identified, the information was added to a dendrogram (a funny-looking graph, shown below) to illustrate the level of similarity between strains. The researchers also estimated the time it took different strains to evolve by comparing the average rate of mutation and reproduction time for T. delbrueckii to the level of genetic difference between each strain.

The dendrogram shows four clear clusters of yeast strains heavily linked to each sample’s origin. Two groups contain most of the strains isolated from Nature, but can be distinguished from each other by those collected on the American continents (nature Americas group) and those collected in Europe, Asia, and Africa (nature Old World group). The other two clusters include strains collected from food and drink samples, but cannot be discriminated by geographic location. The grape/wine group contains 27 strains isolated from grape habitats in the major wine-producing regions of the world: Europe, California, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. The bioprocess group contains geographically diverse strains collected from other areas of food processing—such as bread products, spoiled food, and fermented beverages—and includes a subgroup of strains used specifically for dairy products. Further analysis of the variation between strains confirmed that, while the clusters don’t perfectly segregate the strains according to human usage, and geographic origin of the sample played some role in diversity, a large part of the population’s structure is explained by the material source of the strain.

Divergence times calculated for the different groups further emphasize the connection between human adoption of T. delbrueckii yeast and the continued evolution of this species. The grape/wine cluster of strains diverged from the Old World group approximately 1900 years ago, aligning with the expansion of the Roman Empire, and the spread of Vitis vinifera, or the common grape, alongside. The bioprocesses group diverged much earlier, an estimated four millennia ago (around the Neolithic era), showing that yeast was used for food production long before it was domesticated for wine making.

While T. delbrueckii has often been overlooked by winemakers in favor of the more common S. cerevisiae, it has recently been gaining traction for its ability to reduce levels of volatile compounds that negatively affect wine’s flavor and scent. It has also been shown to have a high freezing tolerance when used as a leavening agent, making it of great interest to companies attempting to successfully freeze and transport dough. Though attempts to develop improved strains of this yeast for commercial use have already begun, we previously lacked an understanding of its life-cycle and reproductive habits. In creating this T. delbrueckii family tree, the authors also gained a deeper understanding of the species’ existence, which may help with further development for technological use.

Yeast has weaseled its way into our hearts via our stomachs, and it seems that, in return, we have fully worked our way into its identity. With a bit of teamwork, and perhaps a splash of genetic tweaking, we can continue this fruitful relationship and pursue new opportunities in Epicureanism. I think we would all drink to that!

Related Links:

The Vineyard Yeast Microbiome, a Mixed Model Microbial Map

Reference: Albertin W, Chasseriaud L, Comte G, Panfili A, Delcamp A, et al. (2014) Winemaking and Bioprocesses Strongly Shaped the Genetic Diversity of the Ubiquitous Yeast Torulaspora delbrueckii. PLoS ONE 9(4): e94246. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094246

Image 1: Figure 1 from article

Image 2: Figure 3 from article