Sharing is Caring: Varied Diets in Dinosaurs Promoted Coexistence

Everyone loves a good dinosaur discovery. Though they’re few and far between, sometimes we get lucky, finding feather imprints, mohawks, or birthing sites that reinvigorate public interest and provide bursts of insight about how they ruled the Earth before our arrival.

Dinosaurs must have been doing something right because they coexisted for millions of years, much longer than we humans have even been on the planet. In an article recently published in PLOS ONE, University of Calgary researchers studied markings on dinosaur teeth to determine how a diverse group of megaherbivores—plant-eating species whose adults weighed in at over 1,000kg—was able to coexist in Canada for at least 1.5 million years. The authors’ findings suggest that these dinosaurs managed to last so long by eating things that the others didn’t, thereby reducing competition for food and promoting a more harmonious (if dinosaur life could be considered so) coexistence.

The authors of this study started by taking a look at general tooth shape and any markings visible to the naked eye before moving onto examine the microscopic markings on teeth. The presence of certain small shapes or marks on teeth may indicate what type of food an individual ate during its lifetime, and can be analyzed using a technique called microwear analysis. As you might guess, foods with different textures or hardness leave different markings on our teeth. For instance, pits in the teeth suggest consumption of hard foods like nuts, while scratches are linked to the ingestion of tough leaves or meat. A combination of both reflects a varied diet.

The researchers analyzed a group of 76 fossils from 16 species in three ancestral groups, focusing on teeth still connected to skulls to provide more accurate species identification. These three groups lived together during the Cretaceous period in the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada, which at that point was on an island continent called Laramidia.

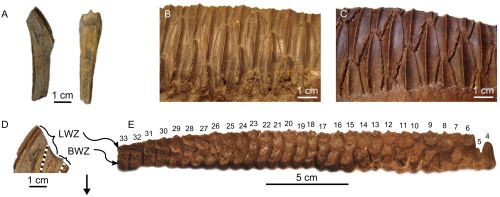

Ankylosauria, whose teeth are seen above, were a group of armored, stocky dinosaurs. One subgroup, the ankylosaurids, had small, cusp-like teeth (marked A) good for eating fruits and softer plant tissues, while another, the nodosaurids (marked B), had blade-like teeth useful for tougher and more fibrous plant tissues. Microwear analysis showed no significant difference between these two subgroups, meaning that, despite differences in general tooth shape, results indicate that their diets did not differ significantly. The evidence of both pits and scratches on their teeth suggests that both ate a variety of fruits and softer foliage.

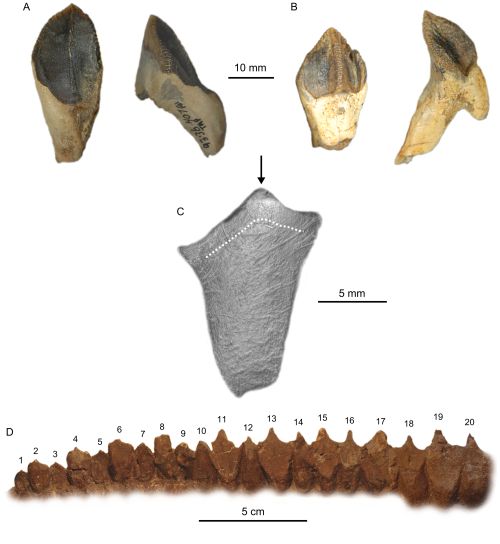

Hadrosauridae—identifiable by their duckbill-shaped face—had similar microwear to the Ankylosauria, suggesting that they also had a generalized diet, though their broad teeth, likely used for crushing food, may have made it easier for them to consume all parts of targeted plants, including stems and seeds, than the cusp or blade-like teeth found in the Ankylosauria.

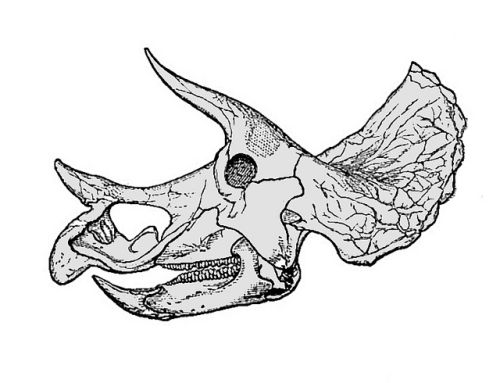

Ceratopsidae, a family of thick-skulled, horned dinosaurs, including the well-known Triceratops, had teeth that functioned as shears, suggesting that they consumed particularly tough plants. Microwear analysis supports this idea, indicating more scratches than pits, and showing that these dinosaurs may have subsisted on mainly rough foliage, like twigs and leaves.

The evidence provided by microwear analysis, incorporated with other known facts about these species, such as height, skull shape, and jaw mechanics, helps paint a broader picture of the dinosaur food scene in Laramidia, and supports previous research suggesting that the varied diets allowed these large species to coexist for 1.5+ million years. Maybe we can take some cues from them to make sure we are at least as successful. Fingers crossed no meteors come along to ruin our chances.

Citation: Mallon JC, Anderson JS (2014) The Functional and Palaeoecological Implications of Tooth Morphology and Wear for the Megaherbivorous Dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (Upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada. PLoS ONE 9(6): e98605. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098605

Image 1: Triceratops prorsus skull by Zachi Evenor

Images 2-4: Figures 1, 9, and 6 from article