You Live in What Kind of Home? A-nem-mo-ne-men… me-ne-mo-nee!

Clownfish Find Refuge among the Toxic Tentacles of Sea Anemones

As we’ve seen in the movies, the world is a dangerous place for a clownfish far away from home. This is all the more reason to ensure that their homes provide adequate protection. What makes a good home for a clownfish, you might ask? Sea anemones. The toxic venom that anemones produce to kill intruders and prey alike provides clownfish with a safe haven. It’s fairly effective too. Clownfish can live for 35 years or more, which is more than three times the lifespan of their similarly sized fish counterparts! That said, not all anemones are created equal, and there are a number of different species that clownfish colonize. So how does a clownfish choose?

In a recent PLOS ONE study, “Searching for a Toxic Key to Unlock the Mystery of Anemonefish and Anemone Symbiosis,” the authors hypothesized that clownfish might choose a home based on the differing levels of toxicity between anemone species. To investigate further, the authors collected nine of the ten anemone species known to host 26 species of clownfish in the genera Amphiprion and Premnas. Next, they retrieved venom samples from the anemones to analyze their levels of toxicity.

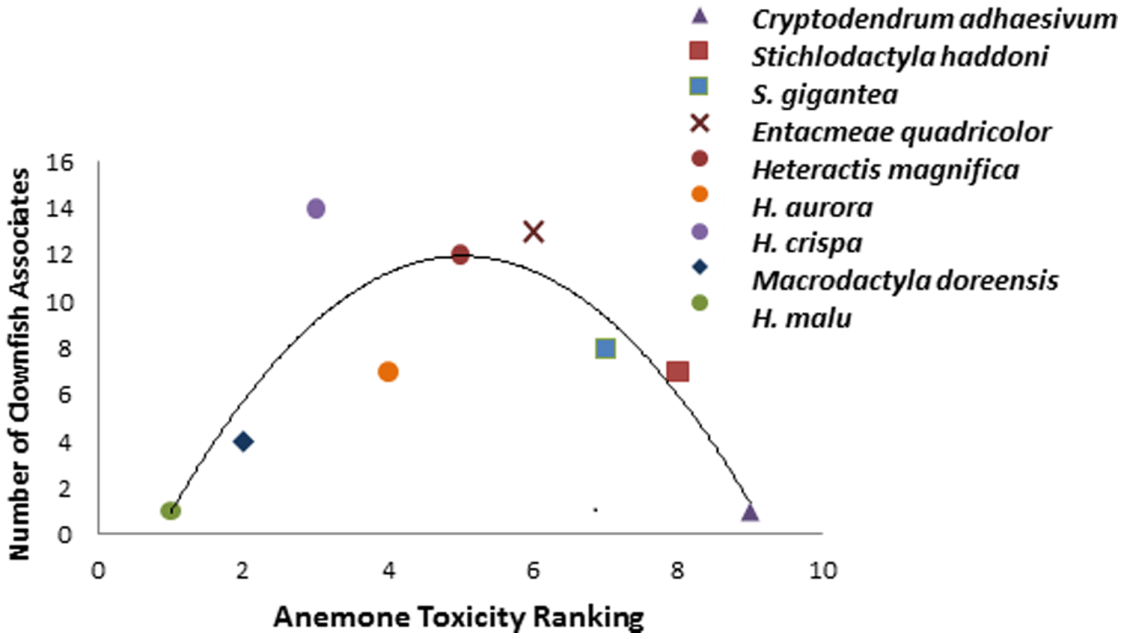

By observing the effects of the various venoms on mammalian cells, brine shrimp, and shore crabs, the authors were able to calculate the relative toxicity of each anemone species. They then compared these findings to the already existing knowledge of how many species of clownfish colonize each anemone species.

They found that anemones that produce an intermediately toxic venom were the ones that hosted the most species of clownfish. Moreover, the least and most toxic anemones hosted the fewest clownfish. The below graph (Figure 4 in the published article) shows the toxicity ranking for each species of anemone that the authors investigated, in relation to how many species of clownfish they host.

The authors believe these results can likely be explained by a balancing act for the clownfish, between the benefits of protection and the costs of withstanding the venom themselves. Living in a highly toxic environment provides protection from predators, though scientists aren’t certain how the clownfish defend themselves against these toxins. Some think that it may have something to do with a protective layer of mucus on their skin. Regardless of the mechanism, few defenses are “free”, meaning that the clownfish likely has to spend energy defending themselves from the same toxins that protect them from predators.

The fish aren’t the only ones with something to gain from this relationship. Anemones with clownfish associates also benefit from increased protection against other species of fish, which may be potential predators. Such relationships are known as symbiotic.

The authors hope their study will spark an interest in anemone toxicity and potentially lead to further research. Additionally, they note the conservation benefits of studying the toxicity of debilitated anemones to gain a better understanding of how human actions impact anemone health. Some concerns for anemones include over-collection and bleaching, a condition that occurs when an anemone’s symbiotic zooxanthellae leave or die.

In the paper, the authors also discuss how the disappearance of host anemone species may either force clownfish to find new host species, or send them into decline. Further research could help us determine whether clownfish are capable of using different species as hosts. Until then, we might remember that “no matter what obstacles you face in life, just keep swimming.”

References

Nedosyko AM, Young JE, Edwards JW, Burke da Silva K (2014) Searching for a Toxic Key to Unlock the Mystery of Anemonefish and Anemone Symbiosis. PLoS ONE 9(5): e98449. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098449

Mebs D (2009) Chemical biology of the mutualistic relationships of sea anemones with fish and crustaceans. Toxicon 54(8): 1071–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.02.027

Images: Images are from Figure 4 of the published article, like NEMO – Daita Saru, Anemonemonemone – Matt Clark, 058 – Anemone, Anemonefish & Divers – Neville Wootton.