Fecal Matters: A Stepping Stool to Understanding Indigenous Cultures

Humans differ by opinions, traits, and baseball team preferences. But one constant factor unifies all humans–we excrete feces, and scientists have recognized that number 2 is number 1 in terms of material for ancient population studies. Humans expel hundreds of grams of feces each day, and prehistory versions of this abundant matter may provide insight into the lives of ancient humans.

Human feces contain DNA from bacteria, fungi, parasites, and even from the human herself. Suspecting that this excrement is rich in biological clues, a group of researchers conducted experiments to investigate fecal microbiomes and published a study in PLOS ONE detailing insights into the diets and lifestyles of two ancient indigenous cultures of Puerto Rico: the Saladoid and Huecoid.

The Huecoid and the Saladoid populations originated from the East Andes and present-day Venezeula, respectively. However, it is believed that they coexisted on the Puerto Rican Island of Vieques for a thousand years, beginning in 5 AD. Although previous studies and artifacts have shown religious and cultural differences between the two populations, notable biological differences had yet to be discovered until now.

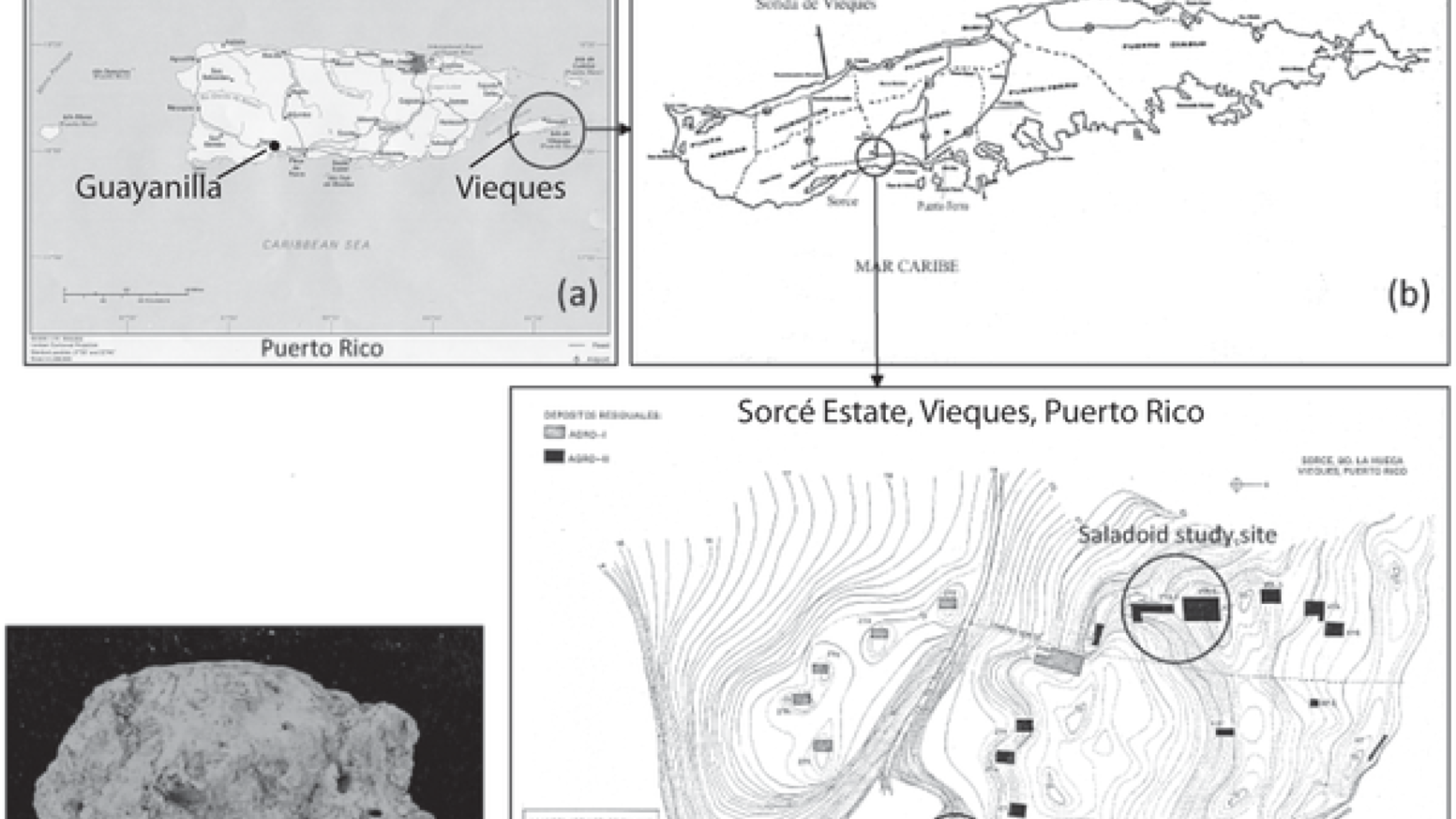

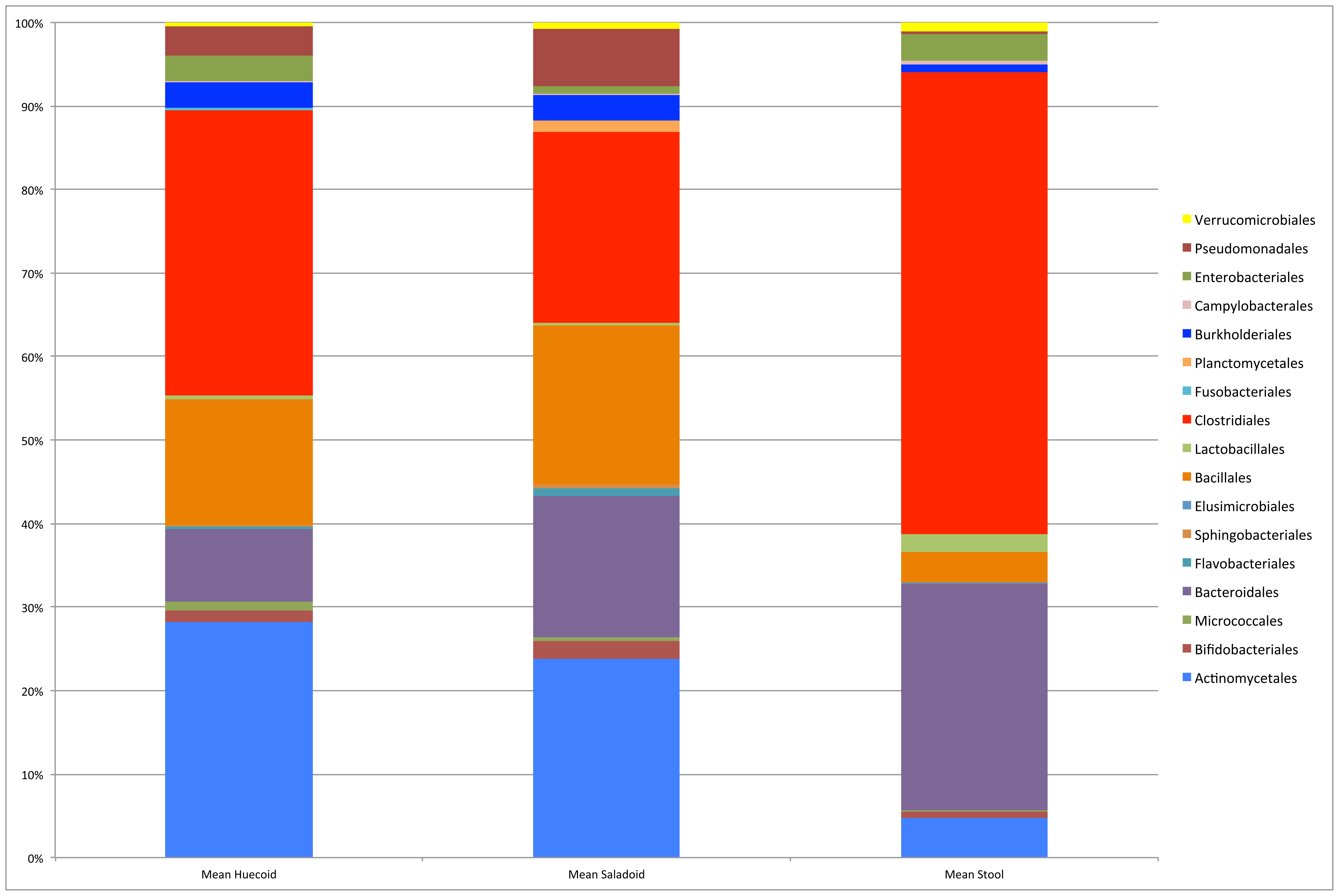

The authors of this study gathered ancient fossilized poop samples, called coprolites, from Vieques and Guayanilla, Puerto Rico, as shown in the image above. Using the excavated samples, the researchers performed DNA sequencing and parasite egg and larva extractions to evaluate the differences in the microbial communities between the two ancient cultures. Contrary to prior belief that a coprolite could not preserve ancient DNA, scientists successfully sequenced the fossil microbes contained in the coprolite core. They found that the bacterial distribution varied significantly between the two cores (as seen in the image above) but most notably, sequencing indicated that the Saladoid population had a 10% higher relative abundance of the bacteria, Bacteroidetes, overall, which may mean that the Saladoid people had a higher protein diet.

Using the remaining coprolite core, the researchers identified parasites based on the shape and presence of dehydrated eggs or larva. According to the authors, the rates of parasite abundance may be double in Saladoid feces as compared to Huecoid. Additionally, the Saladoid core consistently contained hookworms, fish parasites, and dog parasites, providing evidence that the Saladoid people may have eaten raw fish regularly, and may have had dogs as pets. Perhaps sushi and puppies have long been staples in human life?

Researchers also found quite a different diet in the fecal remains of the Huecoid people. The presence of freshwater parasites and evidence of maize may suggest that the Huecoid ate aquatic plants or freshwater invertebrates, and that they may have helped introduce a grain diet to the island.

As the first image shows, the Saladoid and Huecoid populations lived quite close to each other, making these biological differences in the feces appear even more noteworthy. The authors attribute the distinct microbiotas and parasitism composition to diet and cultural differences such as living arrangements, the way food was handled, and human contact with pets.

Although this is a relatively new field of research, analyzing ancient fossilized fecal matter may be useful for scientists trying to characterize indigenous diets and lifestyles. What was previously disregarded as waste may now be considered a trove of historical and scientific data; the clue is in the poo.

Related Content:

http://www.iflscience.com/plants-and-animals/fossilized-feces-differ-among-ancient-cultures

Citation: Cano RJ, Rivera-Perez J, Toranzos GA, Santiago-Rodriguez TM, Narganes-Storde YM, et al. (2014) Paleomicrobiology: Revealing Fecal Microbiomes of Ancient Indigenous Cultures. PLoS ONE 9(9): e106833. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106833

Images: Images are from Figure 1, Figure 4, and Table 5 of the published paper.