Heads Up! Earliest Decapitation Case Found In Brazil

Heads were rolling in the Americas much earlier than previously thought. A recently published study in PLOS ONE uncovers a case of ritual decapitation that took place over 9000 years ago, in the ancient rock shelter of Lapa do Santo in Lagoa Santa, Brazil (image below). Though they may look peaceful today, the rocks of Lapa do Santo hold the secrets of a bloody past.

In popular culture as well as in ethnographic literature, decapitation in South America is often associated with warfare. The Munduruku of northern Brazil beheaded their enemies and mummified the heads using hot oil and smoke, afterward decorating and tattooing the heads for use as potent war trophies. The people of the Amazon in Ecuador and Peru made tsantsa, or shrunken heads, from their dead enemies—a practice that caught the attention of European explorers when they arrived in South America (leading to a brisk trade in faked heads), and which continues to have a macabre hold on Western pop culture today. In both cases, publicly displaying trophy heads was an important part of victory, and the heads were imbued with spiritual power relating to hunting abundance and fertility. However, the authors of this PLOS ONE study weren’t convinced that this particular case of decapitation occurred within a war trophy tradition: the unusual circumstances surrounding these remains and the evidence for their origin seem to tell a different story.

Just what did the authors uncover? During the course of the study, the authors exhumed 26 different human burials from Lapa do Santo–of these, Burial 26 may be the oldest known case of ritual decapitation found in South America. The specimen was most likely from a young man, based on its cranial shape and teeth.

Using Strontium (Sr) isotope testing, the authors estimated Burial 26 was likely local to the area: a particular geographical area will have a certain type of Sr present in the soil, which will enter the food chain and replace some of the calcium in the bones and teeth of the animals (like humans) living in the area–by comparing the isotope signature of the Sr in the ground to the Sr in a particular bone, scientists can assess how local the bone is. The authors dated his remains using radiocarbon dating and accelerator mass spectrometry to determine that he may have lived–and died–over 9000 years ago. Most surprisingly, he wasn’t all there.

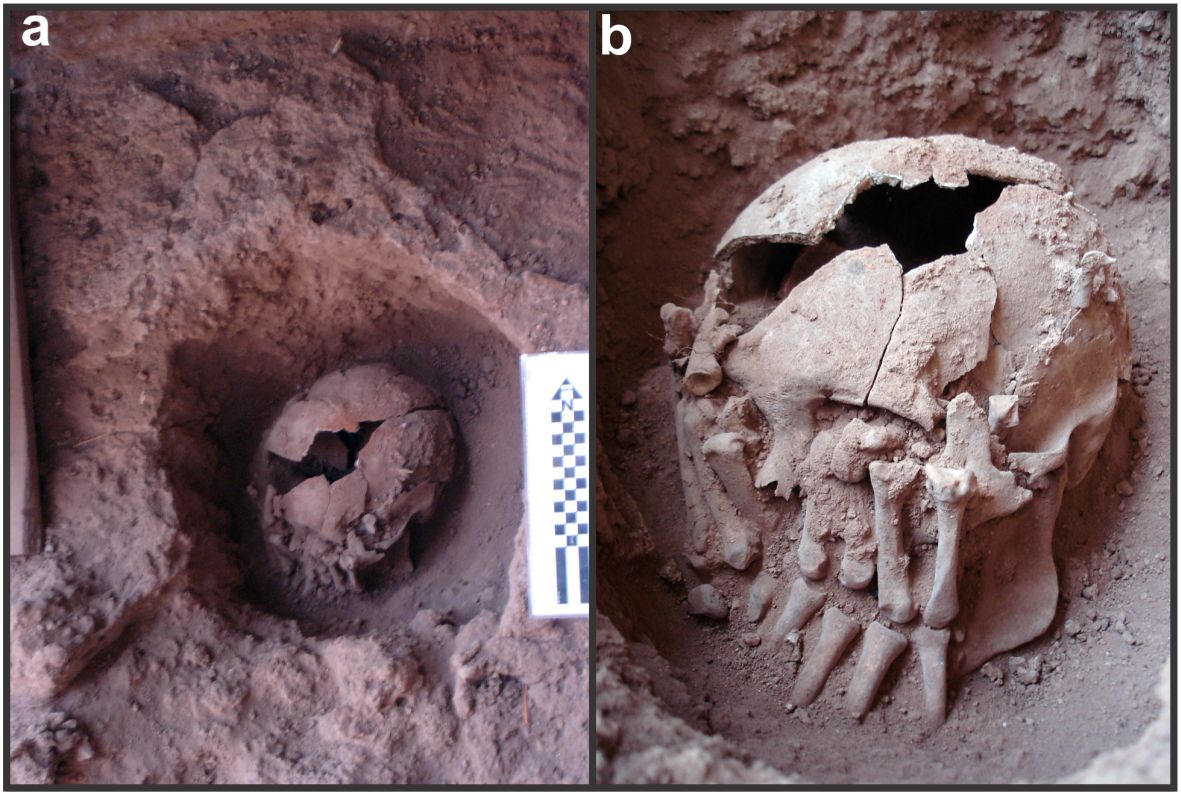

Instead, Burial 26’s severed head, hands, and neck were buried in a shallow, circular grave covered by limestone slabs. His amputated hands rest over his face, arranged in opposition to one another: the fingers of his left hand point up toward his forehead, and the fingers of his right hand point down to his chin. Whatever the intended significance of his hand placement, it’s clear he was deliberately posed.

It’s not obvious how Burial 26’s head and hands were separated from the rest of his body, or what special preparations his remains underwent. There are cut marks to Burial 26’s C6 cervical vertebrae and lower jaw; additionally, his atlas vertebra is fractured and rotated 42 degrees to the left of the axis vertebrae. His hyoid bone, located between the lower jaw and larynx, is absent.

Remarkably, there are relatively few cut marks to Burial 26’s skull and neck when compared to other unequivocal cases of decapitation. Two possible explanations for this observation seem most likely:

- Burial 26’s soft tissue was badly decomposed when he was beheaded, which would have minimized the number of strokes needed to sever his head. However, the presence of delicate articulation in Burial 26’s hand bones suggests almost no soft tissue rot had occurred before his burial.

- The strategy used to remove Burial 26’s head may have been deliberately chosen to minimize cut marks.

To further assess the events around Burial 26’s beheading, the authors used forensics, anatomy, and a unique comparison with a much more recent case of decapitation.

In 2009, Jeffrey Howe was murdered in the UK. His killer dismembered his body, removing his head, both legs, and his right forearm. This case, known as the Jigsaw Murder, was notable due to the precision and skill with which Howe’s body parts were removed by the murderer. When Howe’s skull was found, the only cut marks present were along the lower jaw and sides of the spinal vertebrae; his hyoid bone was missing.

Astute readers will notice this is very similar to the condition of Burial 26’s skull and remaining vertebrae. Although Burial 26’s decapitators are lost to history, Howe’s killer, Stephen Marshall, was caught and sentenced to life imprisonment in 2010. After his sentencing, Marshall confessed to killing and disposing of numerous other victims in his work for a London gang. The authors realized that any information in Marshall’s confession could potentially illuminate this ancient case of decapitation as well.

This detective work paid off: the authors found that Marshall explained exactly how he’d decapitated his victims: using a combination of careful soft tissue cutting and physical force to separate the head from the vertebrae. The similarity of evidence on the bones left behind by Howe and Burial 26 suggests that the decapitators of Burial 26 had related anatomical expertise and might have used the same types of skillful techniques as Marshall to initially sever the soft tissue surrounding the jaw and neck with stone flakes. Additionally, the unique rotation and fracturing of the atlas vertebra as compared to the axis vertebra suggests that the final separation of Burial 26’s head from his body was accomplished using pulling and rotational force.

However, even though Jeffrey Howe’s murder was a violent, criminal act, it would be a misinterpretation to assume that Burial 26’s death and dismemberment occurred under similar circumstances: decapitation has always been a complex act in the Americas. In this case, Burial 26’s status as a local to the area, the lack of any drill holes for cord hanging, and the careful arrangement of his hands over his face suggest that his final end was not as a trophy head collected at war, but instead as part of a sophisticated mortuary ritual at Lapa do Santo. Though it may appear gruesome to modern readers, Burial 26’s death may not have been a murder at all.

The authors propose that these rituals possibly involved public display–Burial 26 may have been a venerated ancestor of his people or other high-status individual, whose physical remains were used for an expression of his community’s cosmological principles around death. And Burial 26’s power to communicate is clearly vast: even 9000 years after his death, his bones are still speaking to us.

Citation: Strauss A, Oliveira RE, Bernardo DV, Salazar-García DC, Talamo S, Jaouen K, et al. (2015) The Oldest Case of Decapitation in the New World (Lapa do Santo, East-Central Brazil). PLoS ONE 10(9): e0137456. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0137456