Insights from the daily grind: what koala and kangaroo teeth can tell us

In their recent study published in PLOS ONE, paleoecologist Larisa DeSantis and her team find out whether diet and climate have an effect on tooth wear in two species of kangaroo and one species of koala.

Gnashers, pearly whites, chompers, call them what you like, but teeth are important bits of bodily equipment. Most animals will use them on a daily basis and whether they’re tearing into a piece of meat or chewing away at vegetation, the very act of eating can have a big effect on teeth. So much so that characteristic wear and tear can be used to distinguish between different types of diets and possibly even the ecological environment of the animal. Furthermore, by characterizing teeth of modern-day extant animals, paleontologists can begin to infer the diets and ecological niches of extinct animals.

It is this area of paleontology that is of interest for paleoecologist Larisa DeSantis from Vanderbilt University, USA. Dr. DeSantis is an Assistant Professor at the Tennessee university and is currently undertaking a research project aimed at characterizing teeth from a wide variety of marsupials including kangaroos, possums and koalas. DeSantis also teaches a course, “Paleoecological Methods”, to graduate and undergraduate students to highlight the many ways that researchers can reconstruct ancient environments from measurements of tooth wear, stable isotopes, pollen and other materials. DeSantis’ grant places a large emphasis on integrating research into education and so instead of writing term papers DeSantis involves the students in a research project during the semester. She highlights the advantages of this approach saying, “Doing research allows students, most of whom haven’t yet published scientific papers, to gain primary experience designing a study, gathering data, analysing results and communicating the study design, methods, and results in written and oral form.”

For the group undertaking the course in the fall of 2017, they decided to focus on investigating teeth from two different species of extant kangaroo, the eastern gray kangaroo, Macropus giganteus and the western gray kangaroo, Macropus fulignosis and compare them to teeth from Phascolarctos cinereus, a species of koala – across the broad geographic ranges of these species. The research team wanted to see if koalas and kangaroos could be distinguished from one another and whether patterns of tooth wear varied between different climatic conditions. For the study, the students focused on one type of dental wear called mesowear. This type of measurement focuses on two different characteristics of teeth, namely cusp shape and cusp relief. Cusp shape can be defined as sharp, round or blunt and cusp relief, the gradient of the slope between the top of the cusp the base, was classified as high, medium and or low. DeSantis explains why they chose these measurements, saying “dental mesowear can be taught to students within a few minutes and benefits from multiple individuals scoring the same teeth according to dental mesowear metrics.”

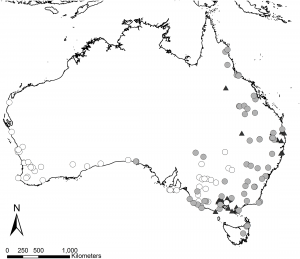

Armed with knowledge of this methodology, the team of students set about examining photographs and dental moulds taken from mandibles stored in several museums. In total, they measured the cusp shape and relief from the lower jawbones of 71 M. fulignosis specimens, 96 M. giganteus specimens and 46 mandibles from P. cinereus. All the specimens were collected from a broad geographic range across Australia at varying latitudes and longitudes. Using this information, they also gathered climatic data, such as mean annual precipitation and mean maximum and minimum temperature from the closest weather stations to where the specimen was originally collected.

DeSantis and her team of students found that they could easily distinguish between koalas and kangaroos, with kangaroos having lower cusp relief and blunter shapes than koalas. Thinking of their diet, the team points out that this makes sense; kangaroos are known grazers and mixed-feeders with diets high in grass which has a fibrous nature and high silica content which increases abrasion of the teeth. In contrast, koalas are browsers and the koala’s studied specifically prefer eucalyptus, a food source lacking silica in the leaves. However, grass and eucalyptus can have lots of dust or grit on the surface, especially in dry regions where precipitation and/or relative humidity is low. Thus, the team set out to test if dental mesowear in these marsupials was reflective of food consumed or if local climate was instead influencing dental mesowear.

When the researchers looked to see if climatic variables affected mesowear they didn’t see much change. Specimens collected from more arid locations didn’t show a blunter profile than those collected in wetter regions. Instead, they did find some correlation between temperature and mesowear in koala and M. giganteus teeth. These data showed that teeth from koalas in warmer regions have higher relief, suggesting that the teeth are less worn down in these conditions. This might be because in warmer conditions, koalas need to replenish the water lost by evaporative cooling and eat plants with a higher water content. Whilst the change in the koala teeth wasn’t unexpected, the observation that M. giganteus teeth were also less worn down in warmer climates came as a bit of surprise, as these kangaroos are known to feast mainly on abrasive grasses in warmer environments.

Whilst temperature seemed to have a slight effect on mesowear DeSantis concludes that “Dental mesowear in the marsupials we examined do record known dietary behaviour and do not appear to track relative aridity or precipitation. This suggests that diet, not grit on the landscape, is contributing to dental mesowear formation.” This is an important clarification as this is only the second mesowear study conducted on marsupials and extends the prior study to include climatic variables. With these data DeSantis says “this study allows us to interpret the diets of ancient marsupials, in particular kangaroos and koalas, with knowledge that diet is the major signal recorded via mesowear.” However, the research doesn’t stop here and next DeSantis plans to investigate microwear and stable isotopes to see if there are more tell-tale signs that can be used to infer diets of ancient marsupials.

References

DeSantis LRG, Alexander J, Biedron EM, Johnson PS, Frank AS, Martin JM, et al. (2018) Effects of climate on dental mesowear of extant koalas and two broadly distributed kangaroos throughout their geographic range. PLoS ONE 13(8): e0201962.

Featured Image: From PACO ARNOLD SOLARTE from Flickr CC BY 2.0