Two Shark Studies Reveal the Old and Slow

Sharks live in the vast, deep, and dark ocean, and studying these large fish in this environment can be difficult. We may have sharks ‘tweeting’ their location, but we still know relatively little about them. Sharks have been on the planet for over 400 million years and today, there are over 400 species of sharks, but how long do they live, and how do they move? Two recent studies published in in PLOS ONE have addressed some of these basic questions for two very different species of sharks: great whites and megamouths.

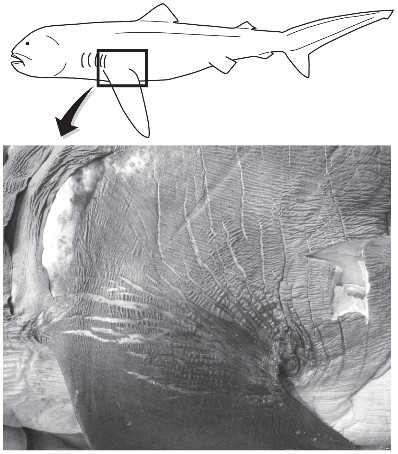

The authors of the first study looked at the lifespan of the great white shark. Normally, a shark’s age is estimated by counting growth bands in their vertebrae (image 1), not unlike counting rings inside a tree trunk. But unfortunately, these bands can be difficult to  differentiate in great whites, so the researchers dated the radiocarbon that they found in them. You might wonder where this carbon-14 (14C) came from, but believe it or not, radiocarbon was deposited in their vertebrae when thermonuclear bombs were detonated in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean during the ‘50s and ’60s. These bands therefore provide age information. Based on the ages of the sharks in the study, the researchers suggest that great whites may live much longer than previously thought. Some male great whites may even live to be over 70 years old, and this may qualify them as one of the longest-living shark species. While these new estimates are impressive, they may also help scientists understand how threats to these long-living sharks may impact the shark population.

differentiate in great whites, so the researchers dated the radiocarbon that they found in them. You might wonder where this carbon-14 (14C) came from, but believe it or not, radiocarbon was deposited in their vertebrae when thermonuclear bombs were detonated in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean during the ‘50s and ’60s. These bands therefore provide age information. Based on the ages of the sharks in the study, the researchers suggest that great whites may live much longer than previously thought. Some male great whites may even live to be over 70 years old, and this may qualify them as one of the longest-living shark species. While these new estimates are impressive, they may also help scientists understand how threats to these long-living sharks may impact the shark population.

A second shark study analyzed the structure of a megamouth shark’s pectoral fin (image 2) to understand and predict their motion through the water. Discovered  in 1976, the megamouth is one of the rarest sharks in the world, and little is known about how they move through the water. We do know that the megamouth lives deep in the ocean and is a filter feeder, moving at very slow speeds to filter out a meal with its large mouth. But swimming slowly in the water is difficult in a similar way flying slowly in an airplane is difficult. Sharks need speed to control lift and movement.

in 1976, the megamouth is one of the rarest sharks in the world, and little is known about how they move through the water. We do know that the megamouth lives deep in the ocean and is a filter feeder, moving at very slow speeds to filter out a meal with its large mouth. But swimming slowly in the water is difficult in a similar way flying slowly in an airplane is difficult. Sharks need speed to control lift and movement.

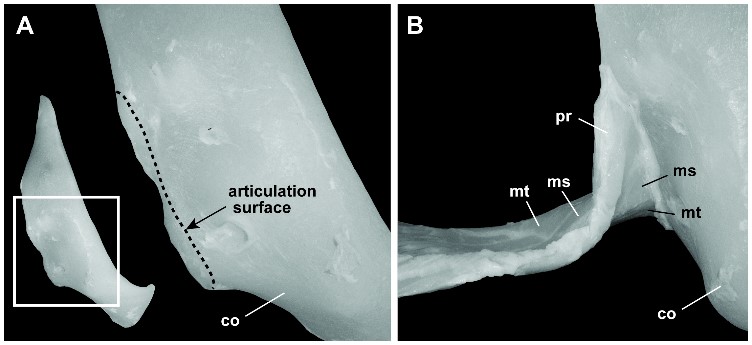

To better understand the megamouth’s slow movement, the researchers measured the cartilage, skin histology, and skeletal structure of the pectoral fins of one female and one male megamouth shark, caught accidentally and preserved for research. The researchers found that the megamouth’s skin was highly elastic, and its cartilage was made of more ‘segments’ than any other known shark, which may provide added flexibility compared to other species.  The authors also suggest that the joint structure (image 3) of the pectoral fin may allow forward and backward rotation, motions that are largely restricted in most sharks. The authors suggest that this flexibility and mobility of the pectoral fin may be specialized for controlling body posture and depth at slow swimming speeds. This is in contrast to the fins of fast-swimming sharks that are generally stiff and immobile.

The authors also suggest that the joint structure (image 3) of the pectoral fin may allow forward and backward rotation, motions that are largely restricted in most sharks. The authors suggest that this flexibility and mobility of the pectoral fin may be specialized for controlling body posture and depth at slow swimming speeds. This is in contrast to the fins of fast-swimming sharks that are generally stiff and immobile.

In addition to the difficulties in exploring deep, dark seas, small sample sizes present challenges for many shark studies, including those described here. But whether studying the infamous great white shark or one of the rare megamouths, both contribute to a growing body of knowledge of these elusive fish.

Images1: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084006.g001