Honey for Your Boo Boo

An apple a day might keep the doctor away, but honey may fight some infections.

Bacterial cell walls are not only responsible for sustaining the cell’s shape but are also necessary for the bacteria’s growth, survival, and reproduction. A class of antibiotics called beta-lactams, which includes the familiar antibiotics penicillin and ampicillin, attack the cell wall’s proteins, causing the cell wall to fall apart and die. While this is effective for treating many common bacterial infections in people, microbes have long been developing resistance to antibiotic drugs, referred to as antibiotic resistance. In the race to protect ourselves from these bugs, scientists are looking for promising alternatives that may combat microbes with the same effectiveness as antibiotics.

Previous studies have investigated honey’s ability to kill and halt growth of certain strains of bacteria. Taking this into account, researchers compared the efficacy of Canadian honey on killing E. coli, strains of bacteria commonly associated with feces and contaminated food, as well as a vital part of all human bodies. The authors of the study, published in PLOS ONE, investigated honey’s antibacterial activity and its potential ability to inhibit growth of antibiotic-resistant strains of E. coli.

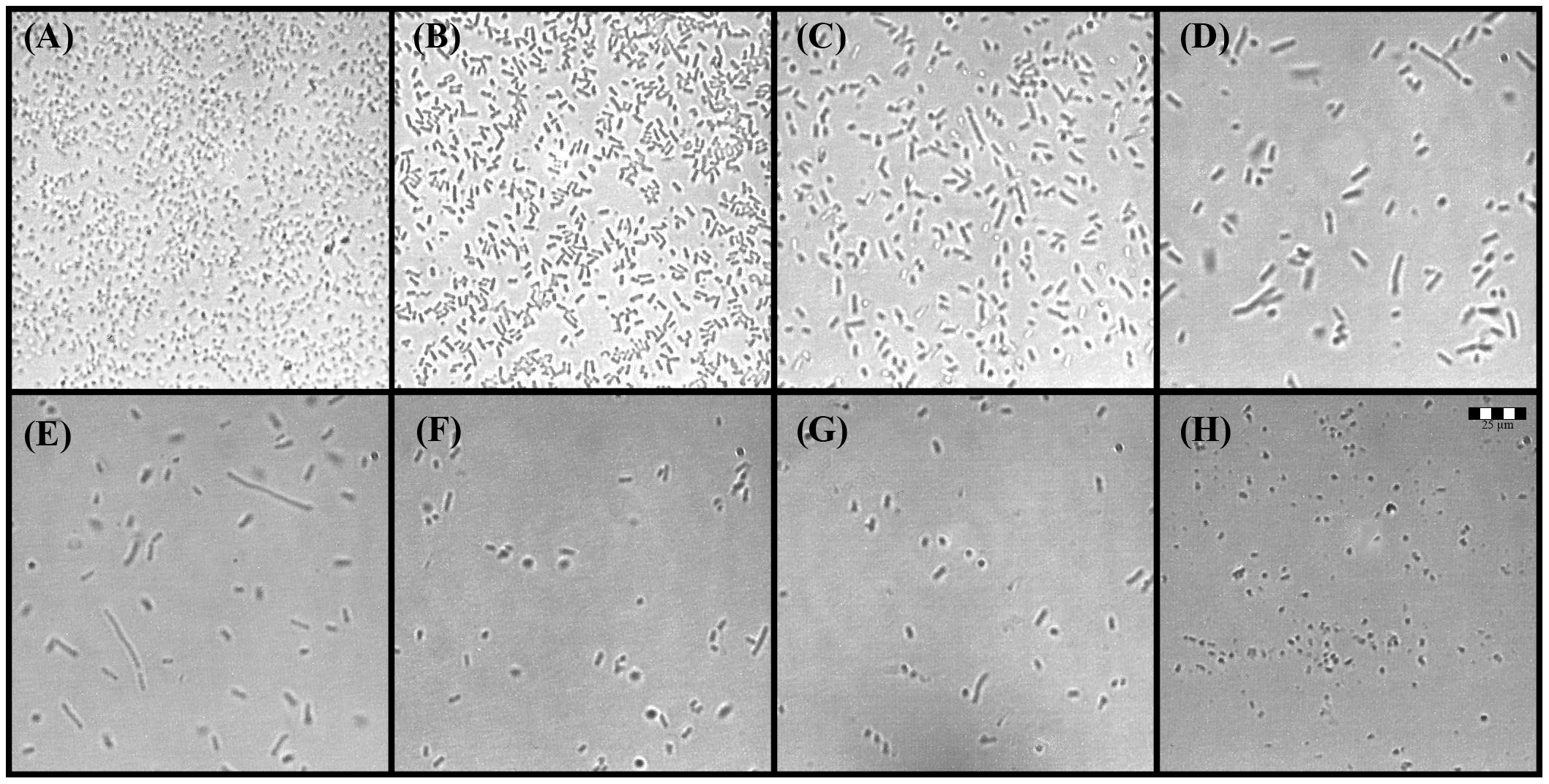

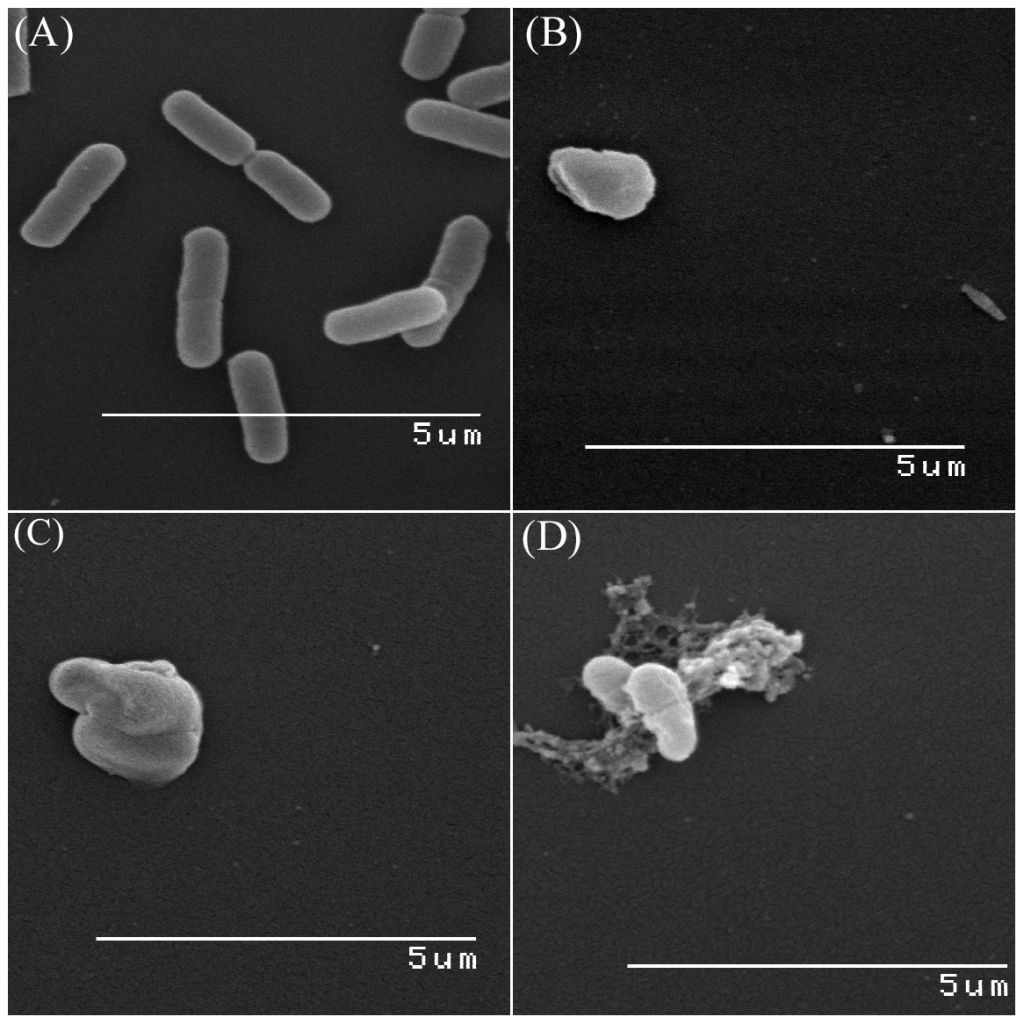

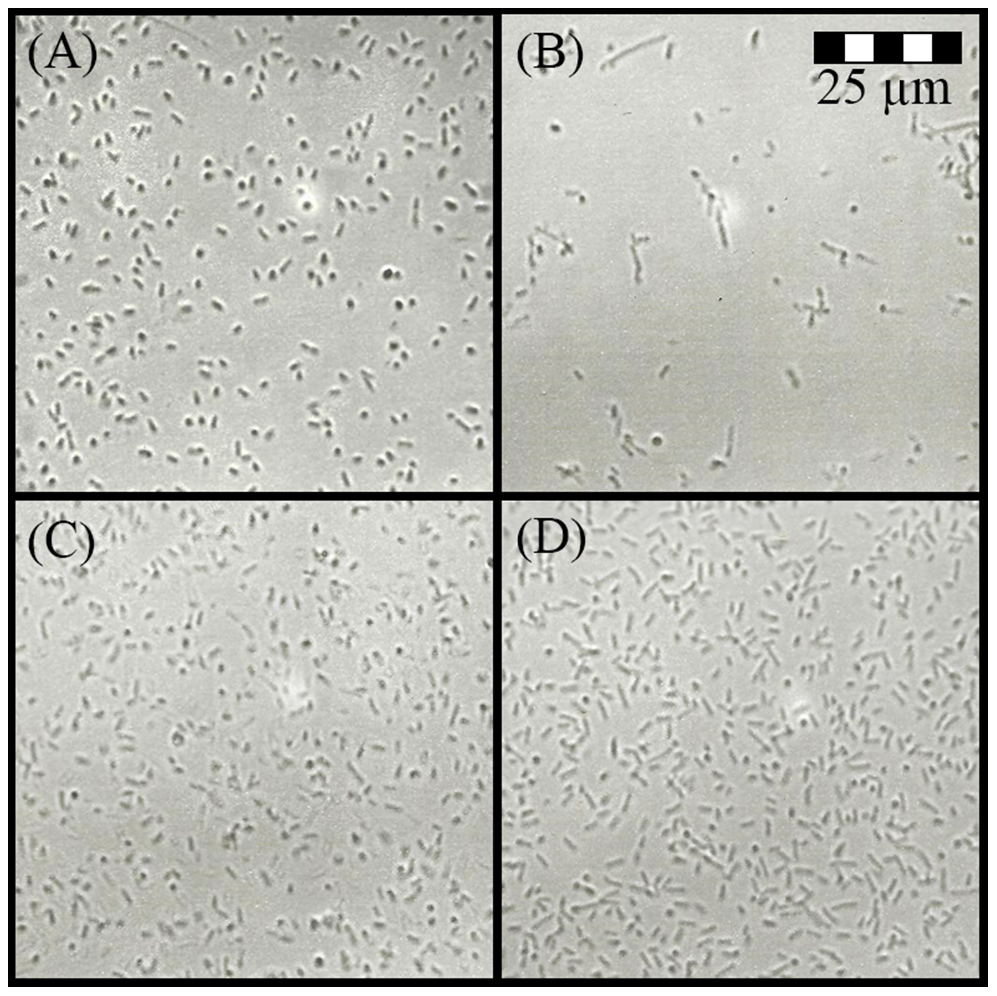

The authors conducted a series of experiments by applying various concentrations of honey or antibiotics to bacterial cell cultures and then visualizing changes in the cell structure to determine the necessary concentrations of each to inhibit growth and kill cells. Using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), as seen in the image above, the authors observed the transformation in cell structure over time as they increased the amount of added honey or ampicillin. Flourishing E. coli are typically rod- shaped with filaments, but within 18 hours of application of honey or ampicillin, the shape appeared to transform into “spheroblasts,” as seen in the image below. Spheroblasts are what remains after the cell wall has been broken by an antibiotic drug, as well as the debris of the dead cell. According to the authors, the results may indicate that like ampicillin, honey can interfere with E. coli’s ability to survive and reproduce.

Many strains of E. coli are resistant to beta-lactams like ampicillin, and to test honey’s effect on these strains, the researchers repeated their experiments with honey on ampicillin-resistant strains of E. coli and again visualized cell shape changes and inhibition of bacterial growth. The honey appeared to halt the growth of the ampicillin-resistant bacteria with the same efficiency as it halted non-resistant strains.

The image above illustrates the destruction of the cell wall and the death of the ampicillin-resistant cell after exposure to honey (panel A before treatment, and panel B after honey application). Recent studies have suggested that honey’s antibacterial mechanisms may be attributed to the concentration difference between honey and water molecules, referred to as high osmolarity, and honey’s ability to inhibit bacterial communication. Honey is a natural mixture of many compounds, and while scientists have yet to confirm the exact compounds responsible, the results of the above study support the idea that honey and ampicillin may have similar antibacterial efficacies, with possibly different mechanisms of attack.

As microbes become increasingly resistant to our standard treatments, it’s important to investigate alternative mechanisms of antibacterial defense. Although more work remains to be done here, the authors’ evidence of honey-induced cell death with apparently similar efficacy to ampicillin may pioneer future studies in the field. In other words, honey could be just what the doctor ordered.

Citation: Brudzynski K, Sjaarda C (2014) Antibacterial Compounds of Canadian Honeys Target Bacterial Cell Wall Inducing Phenotype Changes, Growth Inhibition and Cell Lysis That Resemble Action of β-Lactam Antibiotics. PLoS ONE 9(9): e106967. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106967

Image 1: Viscosity Manifest by Beny Shlevich

Images 2-4: Figures 3, 5, and 9 from the article