Country Food Sharing in the Canadian Arctic: Does it Feed the Neediest?

About 750 Inuit call Kangiqsujuaq, Nunavik, Canada on Quebec’s Ungava Peninsula, their remote, arctic home. Because there are no roads to their community, the Kangiqsujuarmiuts hunt, fish, and forage for most of their food. Artic char, caribou, and seal account for about 58% of total meat intake in the village and are considered “country foods.” The sale of country foods is prohibited by the land claim agreement in the region. Therefore, a Kangiqsujuarmiut must be able to harvest these foods themselves or access them through a food-sharing network.

Historically, indigenous populations in the difficult subsistence environments of the Arctic have had strong social norms around the sharing of food. However, exactly how food sharing networks facilitate the flow of resources throughout the community has not been well studied. Over the next 30 years, climate models suggest that coastal erosion and melting sea ice will have major impacts on food security in this region by disrupting the availability of and access to the traditional Inuit dietary staples. Therefore, it is important to understand how food sharing buffers modern hunter-gatherer populations like the Kangiqsujuarmiut from climate change risk.

To shed light on these questions, anthropologist Elspeth Ready from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln spent a year in Kangiqsujuaq examining the size, quality, and density of the food sharing networks of 109 households in the village. She asked each to list their most important food sharing partners, measured household harvest production over the year (in kilocalories), and calculated household wealth by counting the number of all-terrain vehicles, snowmobiles, cars/trucks, fishing boats, and freighter canoes owned by the household.

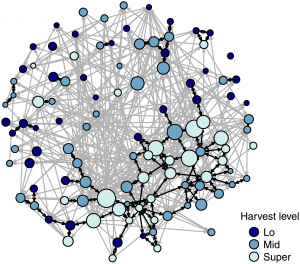

From the data collected, Ready was able to construct the above food sharing network for the community, composed of 500 unique ties among 109 households of varying harvest levels. She found a mean of 4.54 ties per household for both giving and receiving, although ties per household ranged from 0 to 32 ties for giving and 0 to 16 ties for receiving. Interestingly, households that had more out-going food sharing ties also had more incoming ties. In fact, giving away food was the strongest predictor of a large network size.

The ability of Inuit households to participate in food harvesting activities is highly dependent upon access to land, cash, and equipment as well as individual harvesting knowledge, interest, and ability. Villagers who cannot access land or do not harvest food on their own—such as single women with dependents and elders—had the largest food sharing networks in the village. However, single women’s networks were of slightly lower quality, and were comprised of fewer ties to high harvest households. Surprisingly, the main driver of food sharing behavior in Kangiqsujuaq was not “trickle-down” sharing, whereby those with lower wealth or harvest production receive food from higher harvest households. Instead, Ready found that reciprocity and kinship ties between high harvest households were the principle driver for food-sharing. The study results therefore suggest that households with lower wealth and harvest production may also be less able to access country foods through sharing networks.

Ready’s important research sheds light on how, why, and when food sharing networks buffer households from resource shocks. If food resources do not “trickle-down” through sharing networks to households in need, this may mean that low resource households will be more vulnerable to changes in food availability associated with climate change. In 2013- 2014, 41% of Kangiqsujuarmiut had low or very low food security. Poverty and food insecurity are serious social problems in Kangiqsujuaq that may only be partially addressed by traditional food sharing institutions. In the coming years, this remote northern community will see additional challenges that promise to impact the dynamics of food sharing networks—climate change, population growth, health transitions, and further integration with the cash economy. Ready’s study offers a critically important lesson: traditional food sharing institutions may not buffer the most vulnerable members of indigenous communities against access climate challenges to subsistence resources, despite a strong regional ethic of mutual aid.

References:

Ready E (2018) Sharing-based social capital associated with harvest production and wealth in the Canadian Arctic. PLoS ONE 13(3): e0193759.

Featured Image:

peupleloup flickr CC BY-SA 2.0